Nelly’s, A Greek photographer

By Despina Metaxa, Press Advisor to the Minister of Foreign Affairs.

I met Nelly’s in an old courtyard of Plaka. Her photography did not then appeal to me. It was too traditional for my aesthetics, too conservative. At the time, I was attracted by the surrealists and the study of the dark side of life and dreams: she was miles away from that.

Later I saw her photos of refugee settlements. I saw in her a photographer who was able to mitigate the sorrow of desolation. This is how my relationship with her began; anyway, feelings bind people more strongly to one another than techniques.

Nelly Sougioultzoglou is born in Aidini of Asia Minor, in 1899. In 1912 she finds herself a pupil at the Omirio Girl’s School of Smyrni and in 1919 she lives through the destruction of her homeland by the Turks. The daughter of the wealthy merchant Christos Sougioultzoglou then leaves for Dresden to study music and painting. In 1922 her family settles in Athens and Nelly decides to study photography, hoping to make a living out of it. Her teacher is initially the well-known Hugo Erfurt. Later she is tutored by the modernist Franz Fiedler.

Miss Sougioultzoglou returns to Greece in 1924 and opens her first photo studio in Ermou St. The city’s bourgeoisie considers it a sign of fine taste to have their portraits done by the young artist who at the same time practices her art by taking pictures of ancient monuments and small yards of Athenian houses. It is thus that Nelly’s era begins.

When a well-mannered bourgeois scandalizes

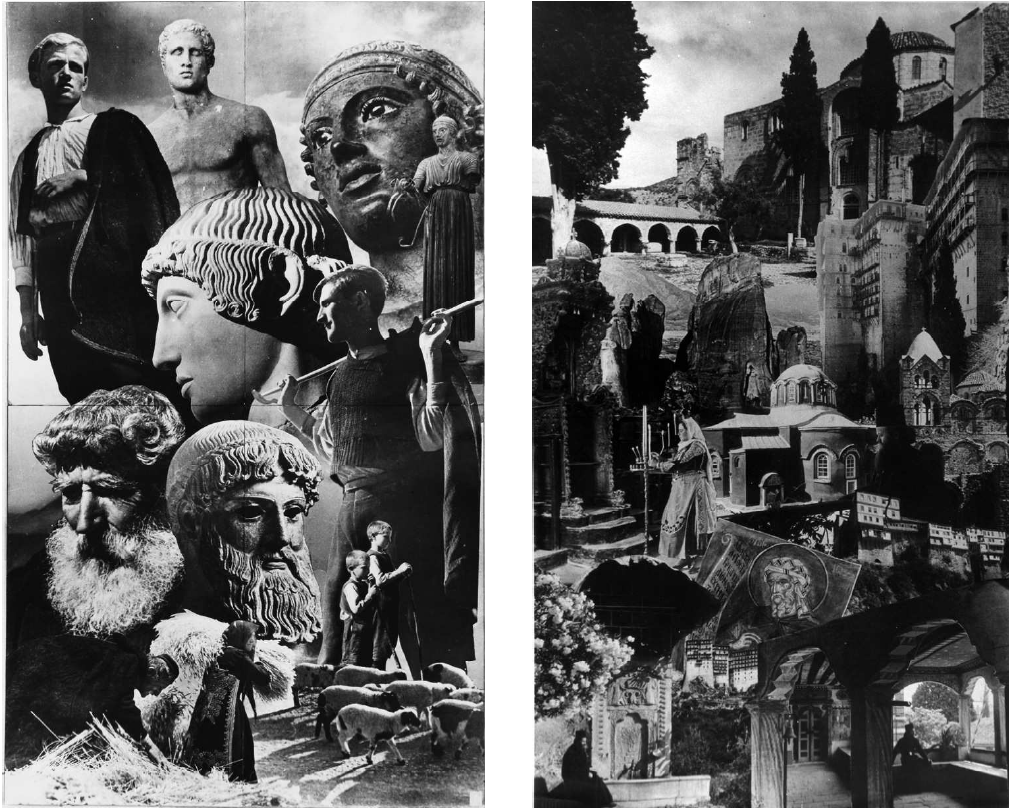

Nelly’s focuses on the pure orders of the Acropolis monuments that fascinate her. She soon decides to give them a face and set them in motion. She meets Mona Paiva, the Comedie Francaise dancer, and suggests to her that it would be a good idea if she could pose for her in the nude on the holy rock. Permission is granted by the authorities as she is by then well known and accepted by the Athens high society. Paiva obliges, and starts to dance inside the Parthenon holding an olive branch. The Leica of Nelly’s captures her smooth motion, creating a series of unique shots. The dancer takes with her this exceptional piece of work, which will be published a little later in a French illustrated magazine. The scandal breaks out immediately in prudish Athenian society.

There is an outcry against the desecration of a holy area, but a number of people, such as Pavlos Nirvanas, speak out in her favour. ”I imagine on the one hand,” he wrote, ”the beautiful priestess, unfastening her girdle in front of Apollo, throwing all the robes covering her divine nudity and bathing in the light, a body like a statue and a rosy complexion like the smile of dawn. And on the other hand I see respectable gentlemen sitting around a table, scratching their heads and writing about desecration. Desecration would occur if, in the throes of archaeological enthusiasm, they happened to throw off their clothes on the Parthenon marbles and pretended to be Hermes of Praxiteles…”

The uproar subsides as time goes by and Nelly’s repeats her attempt. This time she uses as a model the Hungarian dancer Nikolska–dressed up in fine-woven clothes–thus providing photos that embellish the Greek Tourism Stand at the 1936 Paris exhibition.

Landscapes and people

As early as 1927, Nelly’s is introduced to the spirit of the Delphic feasts, organised by the poet Angelos Sikelianos and his wife, Eva. She begins exploring Greece. She takes pictures of people in their everyday lives that bear her own particular stamp. She records by herself the history of the places she visits simply by taking photographs.

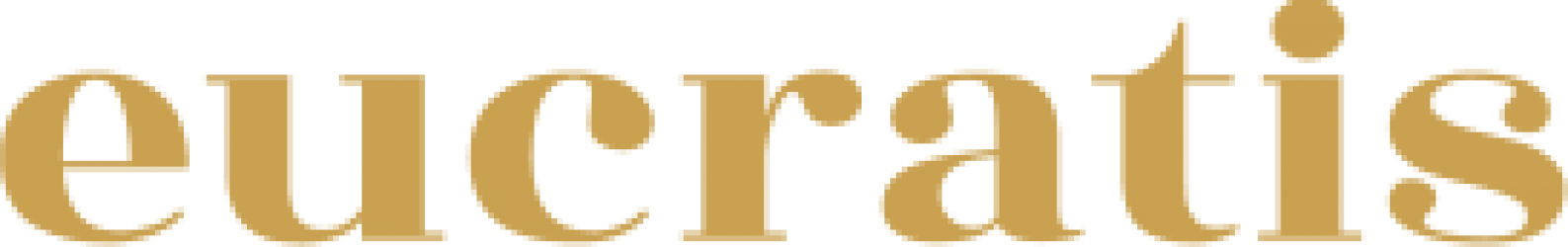

She is fascinated by the Doric landscape and tries to captivate the rich light of the Aegean and the pure figures of the island woman or of the old shepherd. Her purifying idealism contrasts with the reality of her models’ daily life and their experience of hard work. Her art consists of idealising pictures of people, presenting them as free of sadness and pain, and exuding the optimism and the plasticity of classical statues. During this period she works on ‘parallelism’, i.e., she studies the similarities of the ancient Greek statues with Modern Greek types. The characteristics of her method consist of the alternation of plans (close and distant ones), crowning of the picture with architectural elements, vertical human pivots, and staged composition. Nelly’s has not only presented a structured photographic work with a compact style but she has also handed over to posterity a rich folkloric material, with pictures from parts of the country that no longer exist and stories that seem like fairly-tales.

The photographer also deals with the wounds of her old homeland: she creates a unity entitled ‘The yearnings of the Refugees’, depicting the refugee settlements of the Athens neighbourhood of Kessariani.

Refugees from Asia Minor are shown with due restraint and sorrow: not even a hint of melodrama appears in these pictures. Nelly’s has recorded the heart-breaking poverty of these people without forcing the emotions on the viewer. This cycle, coming out of the photographer’s very soul, is distinguished for its almost epic dimension, as it bears witness to the noble fortitude of the refugees in their new difficult conditions.

In Athens, she adored the Acropolis and the old neighbourhood of Plaka. The co-existence of the classical era of antiquity and the era of Byzantine orthodoxy were filtered through the romantic education she received during her years in Germany. Nelly’s created a thematic cycle of approximately sixty photographic representations, which won the enthusiastic comments of the reviewers and the press. The historian Dimitrios Kambouroglou, impressed by the completeness of her collection–which went far beyond the simple worship of ancient monuments–suggested to her a guided tour, historical and emotional, through the cobbled roads of modern Plaka, and its houses with the small yards built in the shadow of the holy rock. These photos were printed by the Bromoil method that she had been taught in Germany. This method consists of a complex procedure used by pictorialists* in order to ensure the uniqueness of the image: through appropriate chemical treatment the paper becomes relief and the photographer, using paintbrushes and oils, intervenes so that the outlines and the gradation of the tones are softened. The result is the appearance of the eerie figures that mark the last aspects of the Romantic Movement.

Portraits

The basically bread-winning occupation of her photography never tied her down to simply recording or beautifying the features of Athens socialites in the inter-war period. Her exceptional style and her theoretical training converted the busy studio of Ermou Street into a workshop of unique photographic experiences. However Nelly’s never gave up her first love, namely, painting: she used her lenses with the fine clarity of the paintbrush, while she lightened each of her models in a unique way. By using the Bromoil method (which already seemed old-fashioned and conservative in the ’20s) she insisted on processing the details of the portraits with the fussiness of a painter. The use of sepia and sanguine helped so that the result does not belong exclusively to either of these two arts.

Her camera immortalises all the personalities of the era: Palamas, Venizelos, Bruno Walter, the members of the royal family, Paxinou and also famous bourgeois and their families. A photo by Nelly’s transcends its ephemeral value and is transformed into a work of art. She herself remained for years attached to her classical education and to her first lessons. She never joined the modernistic movements, such as the surrealists who played havoc with the traditional aesthetic values of Western Europe.

In America

Nelly’s and her husband, the pianist Angelos Seraidaris (they were married in 1929), leave for New York in 1940. Their intention is to stay for a few days but the Second World War breaks out, so they stay there for twenty-seven years. Nelly’s opens a studio in 57th Street and socialises with the Greek community. Once again she finds herself in a new place where she is asked to start from scratch. She has learned how to adjust and she soon becomes known to the Greeks of the city. A genuine lover of Hellenism, she organises exhibitions of her photos from the homeland. The New York Metropolitan Museum shows an interest in them and purchases photos of the Acropolis. She is introduced to Onassis and decorates his tankers, while she also takes photos of the shipowner’s family. Although apparently conservative, she shows interest in new trends and attends photo-reportage classes by Brodovitch. In America, another two collections of hers are born, the ‘Easter Parade’ and the ‘Streets’. The first depicts cute figures of the American metropolis and funny snapshots of a happy and festive New York. The second records the novel forms in the city, the vertical pivots and the geometric perfection. The era of photographing the old city of Athens completes its cycle here with a huge architectural jump through the centuries.

The Seraidaris couple returns to Greece in 1966. Nelly’s stops working. Years later she donates to the Benaki Museum her cameras and her archives. Publications of her work follow suit and the public gets to know the delicate creator of the Acropolis nudes. Nelly’s remains silent and learns to live without the beloved companion of her life. She died in September 1998, at the age of 99.

I do not know if she would have been flattered by the title she was given by some Greeks of ‘the national photographer’. Nelly’s never tried to convert her interest in Greece and its people into a national product. She was simply the child of a place that she loved dearly.

* Pictorialists were photographers of late 19th Century, who considered themselves more as artists and creators of images than recorders of facts. They believed that the artists should compose their images using as their only criterion their aesthetic value.

Source: THESIS (http://www.hri.org/MFA/thesis)

‘parallelism’

the similarities of the ancient Greek statues with Modern Greek types

by Nelly’s